Shelter

A perilous rift is born of the ambiguity of war and peace, the abyss that the essence sinks into. It perishes while the world scatters in panic. In the spaces that we expected to offer us the salvation of values opens the abyss, an absence, an unsprung trap. We slip into the rift between wrongdoing and the crime of omission.

The first year of the war might have passed, but that doesn’t make it any more normal. Time slows down and replicates, day in day out, its soggy banality. We are almost out of rage, fire and enthusiasm, with nothing but mounting exhaustion to replace them. We grow used to anxiety, yet numbness does little to protect. We grow used to grief, yet that doesn’t help either: on the contrary, grief accumulates, adds up, crystallizes.

We got trapped in the time that goes stale and rots without changing. We are so worn down by anxiety that we want to escape not only the war, but also the peace that nurtures the war. Whence does danger come? Even peace is a danger, frayed as it is by the unwavering threat of a yet bigger war. Our chimaera of peace festers in borrowed time, and we’ll yet have to pay for it.

When Bomb Shelter markings started cropping up on the walls in Kyiv, it seemed like a quaint anachronism, a thing straight out of civic defense classes in Soviet schools. Bomb shelters for air raids reminded us that we do still have a quantity of calm, set aside against a rainy day. It’s symbolic that occasionally the markings led nowhere, with not a shelter in sight.

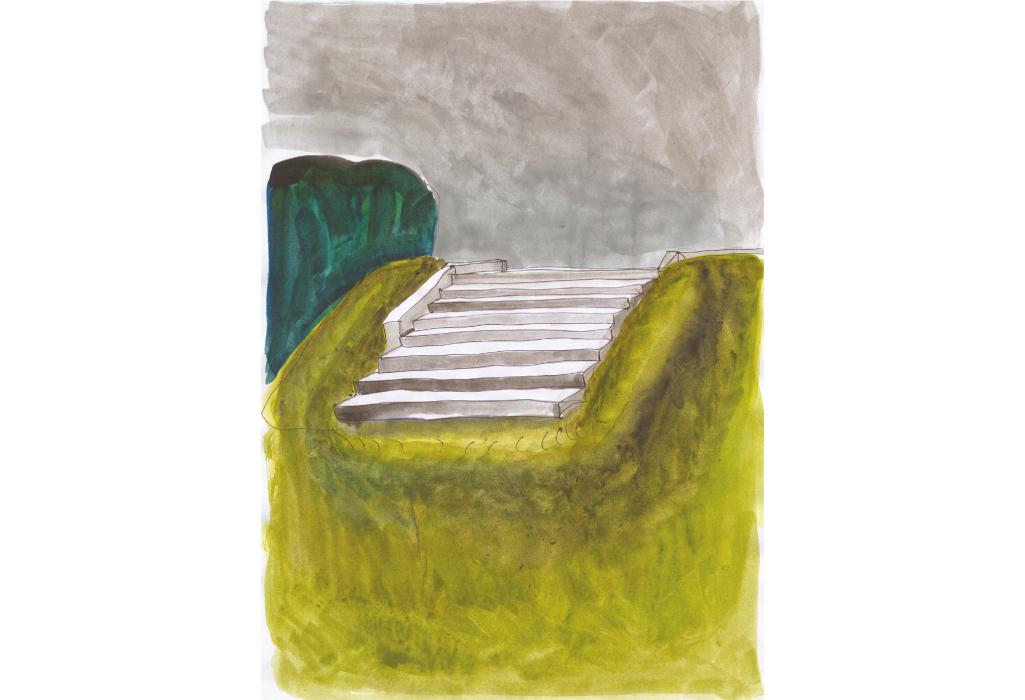

Shelter, the second part of our project, is defined by this search for a shelter in unexpected places, in emptiness (in silence).

We were working on Poet’s Refuge in Kaniv last year, when the events were still unfolding with overwhelming speed. We explored whether poetic language can become a weapon, and what role an artist can play in times that can be described as extreme. We didn’t have time for redefinitions: the world was turning upside down right as we were watching. Everything was changing too fast. Everything seemed to brim with action.

The first year of the war might have passed, but that doesn’t make it any more normal. Time slows down and replicates, day in day out, its soggy banality. We are almost out of rage, fire and enthusiasm, with nothing but mounting exhaustion to replace them. We grow used to anxiety, yet numbness does little to protect. We grow used to grief, yet that doesn’t help either: on the contrary, grief accumulates, adds up, crystallizes.

We got trapped in the time that goes stale and rots without changing. We are so worn down by anxiety that we want to escape not only the war, but also the peace that nurtures the war. Whence does danger come? Even peace is a danger, frayed as it is by the unwavering threat of a yet bigger war. Our chimaera of peace festers in borrowed time, and we’ll yet have to pay for it.

When Bomb Shelter markings started cropping up on the walls in Kyiv, it seemed like a quaint anachronism, a thing straight out of civic defense classes in Soviet schools. Bomb shelters for air raids reminded us that we do still have a quantity of calm, set aside against a rainy day. It’s symbolic that occasionally the markings led nowhere, with not a shelter in sight.

Shelter, the second part of our project, is defined by this search for a shelter in unexpected places, in emptiness (in silence).

We were working on Poet’s Refuge in Kaniv last year, when the events were still unfolding with overwhelming speed. We explored whether poetic language can become a weapon, and what role an artist can play in times that can be described as extreme. We didn’t have time for redefinitions: the world was turning upside down right as we were watching. Everything was changing too fast. Everything seemed to brim with action.

Now events seem to endlessly repeat themselves. We’ve spent the last year in a world whose outlines were washed away by this strange war; reality became muddled, ill defined. After familiar objects exhausted themselves and could no longer serve their functions, we lost our footing. The world wastes and wanes in mundanely devouring itself. It probably can devour itself in ambiguity, because the old familiar definitions no longer apply. Mundane language devolved to inane chatter, no longer fit to narrate or explain.

Artists, however, don’t have a choice but to keep talking to the world and to themselves, not that there’s much of a difference, because only language can shelter both.

Outside of language, the world wastes away, but then, so does artistic language, if the world uses it in vain. (Doesn’t the empty imitation of language remind us of sham bomb shelter signs that imperil the lives of those who can’t tell language and non-language apart?)

We should lead language back to silence, its temporary shelter.

Only artistic language, artists’ haven and shelter, can lay bare the ambiguous world that we’ve found ourselves in. The language itself, however, also needs renewing, since words are depleted of meaning in mundane speech. Such shelters function as the silence and mysterious red lights of dark rooms, in which photographs emerge out of blank surfaces.

Kaniv studios resemble both a dark room and a shelter. Working there feels like descending into an empty shelter, where speaking in silence runs parallel to restless reality. Therefore, we don’t have much of a choice but to try to slip back inside, into the primeval expanse and stillness, where ambiguity has not yet bred anxiety and indifference. To the contrary, it still harbours potential actions and an ability to discern, recognize and define the surrounding objects.

Outside of language, the world wastes away, but then, so does artistic language, if the world uses it in vain. (Doesn’t the empty imitation of language remind us of sham bomb shelter signs that imperil the lives of those who can’t tell language and non-language apart?)

We should lead language back to silence, its temporary shelter.

Only artistic language, artists’ haven and shelter, can lay bare the ambiguous world that we’ve found ourselves in. The language itself, however, also needs renewing, since words are depleted of meaning in mundane speech. Such shelters function as the silence and mysterious red lights of dark rooms, in which photographs emerge out of blank surfaces.

Kaniv studios resemble both a dark room and a shelter. Working there feels like descending into an empty shelter, where speaking in silence runs parallel to restless reality. Therefore, we don’t have much of a choice but to try to slip back inside, into the primeval expanse and stillness, where ambiguity has not yet bred anxiety and indifference. To the contrary, it still harbours potential actions and an ability to discern, recognize and define the surrounding objects.

Wounded healer

Our expectations of art are so specific as to be almost utilitarian. Individual viewers tend to expect aesthetic pleasure, while society demands that art assert, illustrate or affirm its dominant ideology. Art critics assume that art should analyze reality and prod it towards changes. Artists are constantly under scrutiny, as if they are sitting for an exam. That might be true, but the artist need only pass muster with himself, and with history.

History and artists exist in constant tension with each other, with not a chance of catharsis. Only history can pass the final judgments that won’t ever reach the artist. History made Johann Sebastian Bach into the greatest composer of the Baroque period, long after both the style and its other adherents had drifted into obscurity. History made Marquis de Sade into a 20th century philosopher, since that’s the era that was defined, both in deeds and in thoughts, by the colossal projects of the new world and the new man for which humanity had to pay in ghastly mechanistic cruelty.

However, artists also hasten history along. It’s their fate: to denominate, to name the surrounding phenomena. Images precede thought, denominate the future and present it to the world, long before these events, these discoveries come to pass. To name is to prophesy, or to warn.

Artists are the nervous system of humanity: they sense pleasure and pain earlier than the rest of the body.

Artists want to hasten the world along. Why else would they work? Even the vainest among them know that the recognition of contemporaries is but an illusion. In the tragic times of drastic and painful social shifts, artists manifest their essence: they are “wounded healers.” The archetype of Verwundeter Heiler was introduced by a Swiss analyst Adolf Guggenbühl-Craig: it evokes the image of Asclepius, the god of medicine in Greek mythology, who himself suffered from physical pain. Guggenbühl-Craig contends that doctors who have personal experience of an ailment can devise more effective therapy, but the experience also makes them more prone to sadistic outbreaks. However, healing is often impossible without drastic measures, and each artist is prone to sadistic violence. He violates the world with his works, which not a soul had asked for.

Guernica by Pablo Picasso is one of the most important works of the type in the 20th century. It is one of the most penetrating and realistic documents of the era of colossal modernist projects of total revolutions that bled over into total wars.

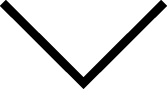

Such conscious violence is typical of the works of Volodymyr Budnikov and Vlada Ralko. They are confident, willful artists, driven by their own sensibilities and the raw will to express, rather than by trends, the logic of an instilled tradition, social demands or even by rational analysis.

Therefore, Budnikov and Ralko cannot be described as a tandem. They stay in dialogue. Yet the dialogue is stripped of all shreds of conformity, both in the microcosm of their conversation and in the broader context of the country or the world. The Shelter Project marks a milestone in their dialogue and highlights its most salient features. Both artists stay true to themselves, and both evoke the catastrophe through their recognizable imagery. There’s no obvious shelter for those caught in it.

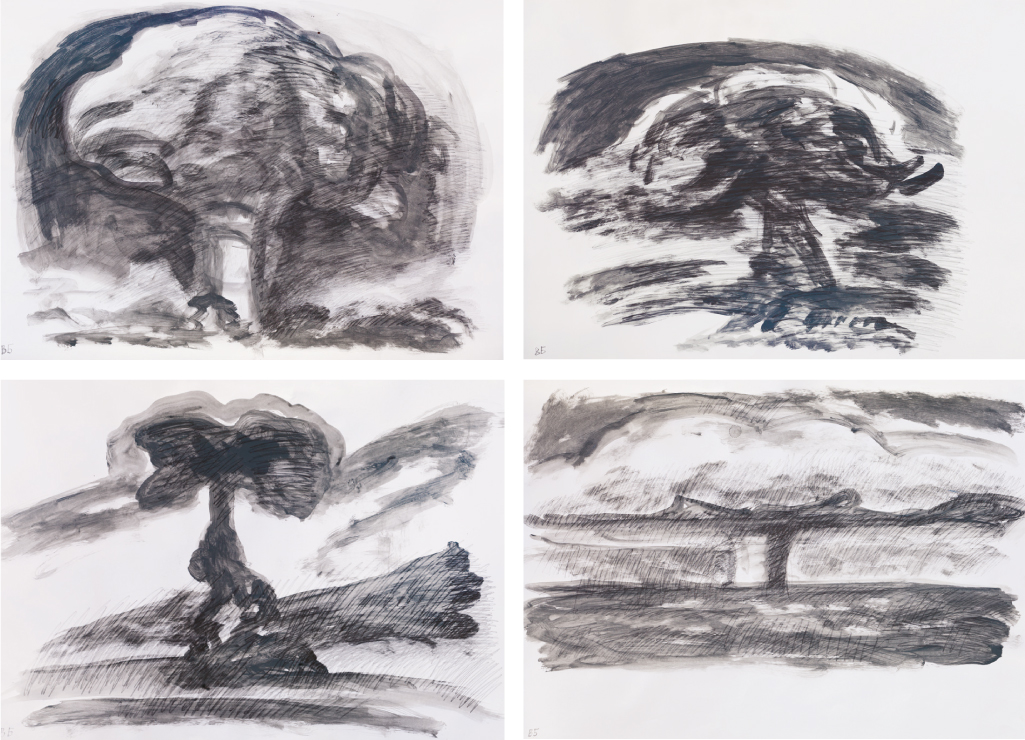

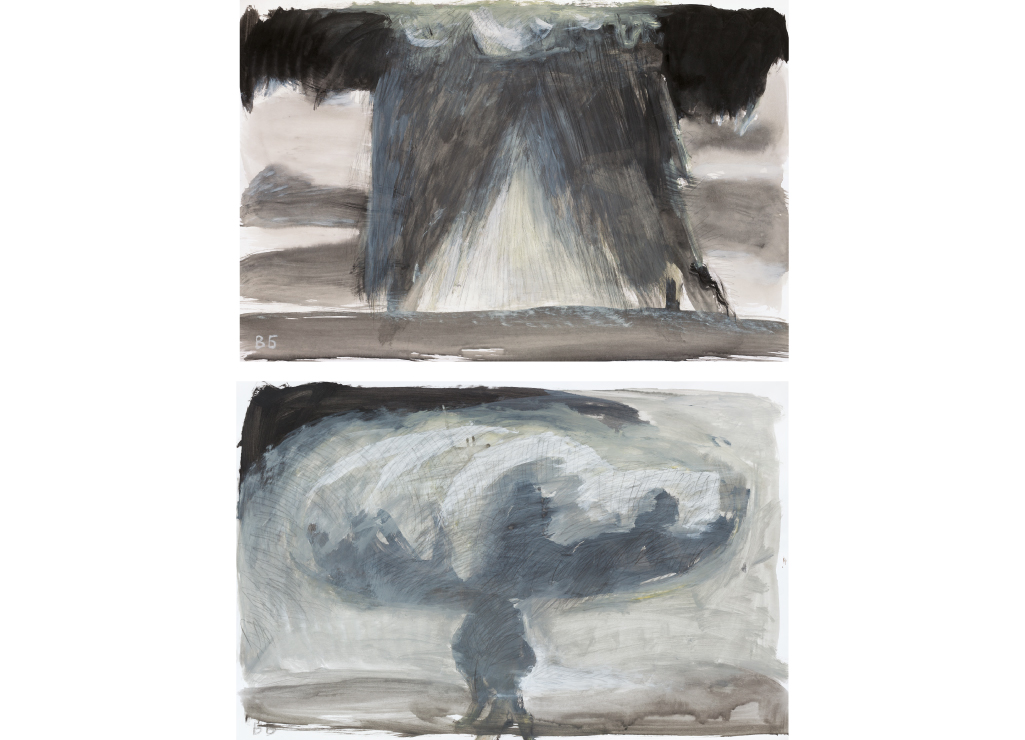

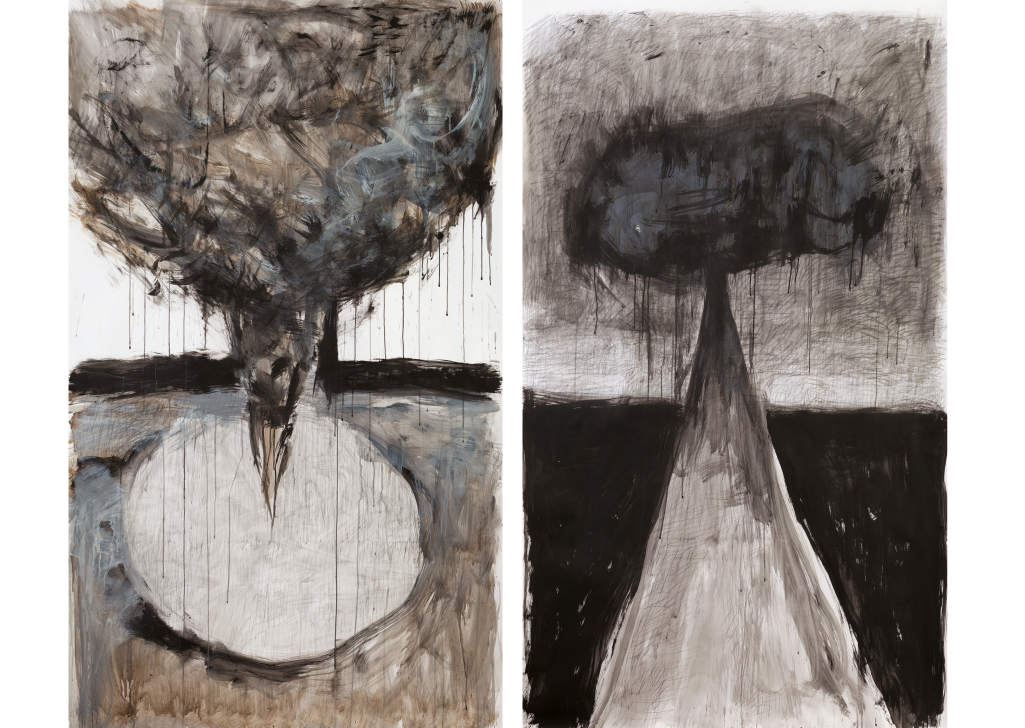

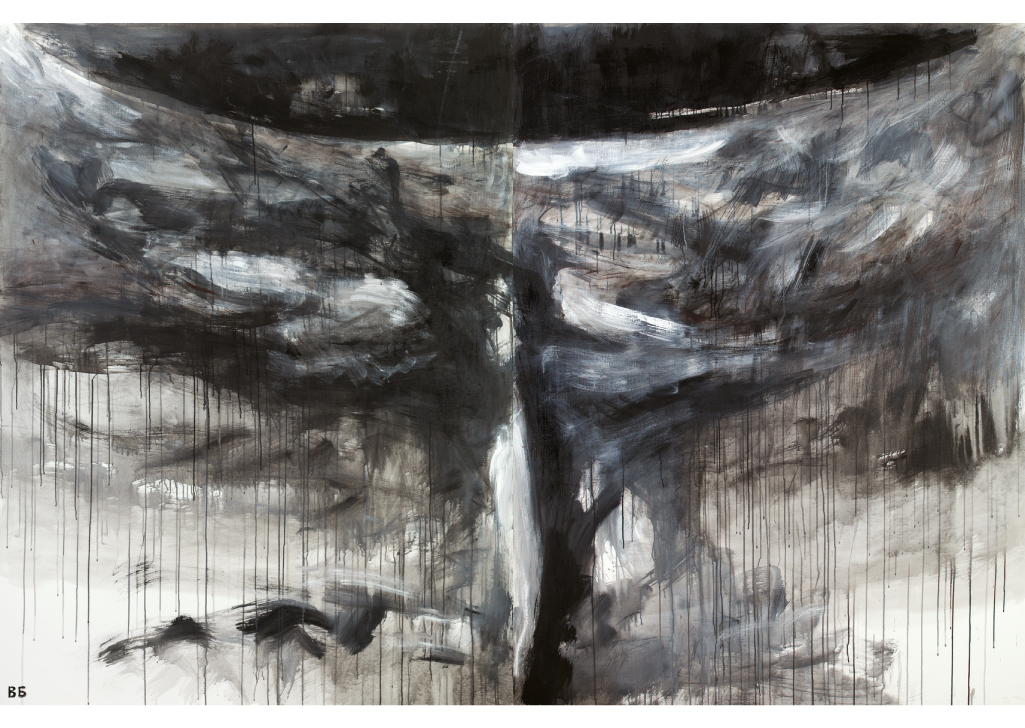

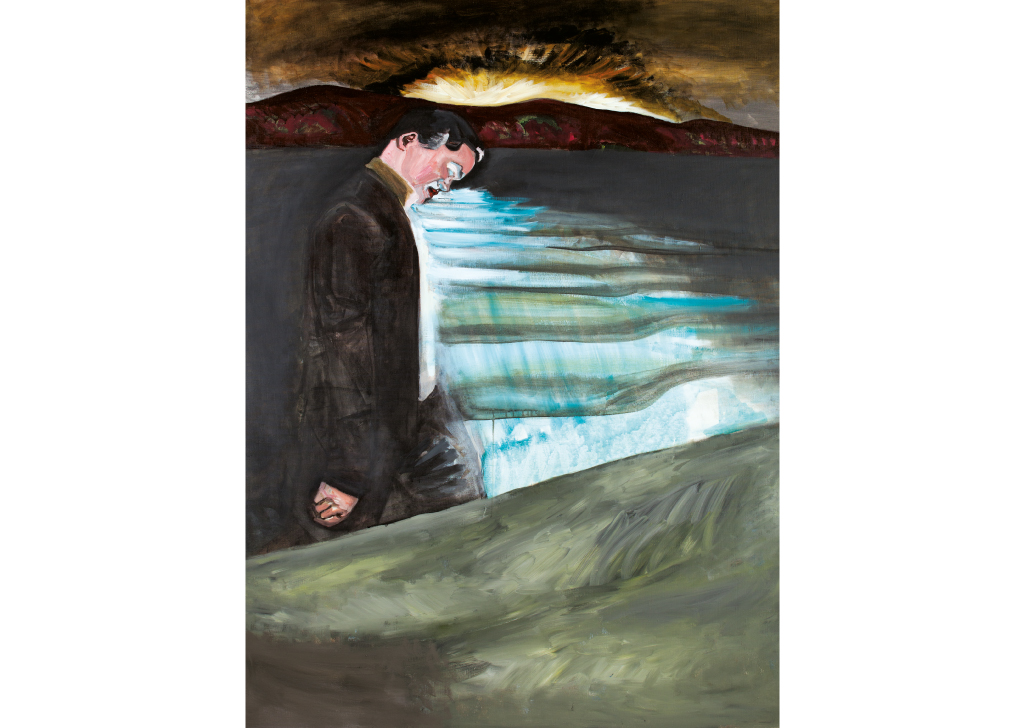

Through all the stages of his career, Volodymyr Budnikov’s sensibility was marked by the understanding of the world as an ongoing catastrophe. He explored the motif through landscapes, through the images of nature, which are always born of the strife of elements and organisms. The scholars of Budnikov’s works are often tempted to mention the Baroque style with its catastrophic worldview. For decades, Budnikov has been exploring the future, with all its unpredictable shifts, anxieties and anguishes, through landscapes. His gaze is unflinching, since he knows that life, in all its anguish and glory, is contained in movement. Each tree that breaks out of its seed in a titanic spasm is in movement. Each boulder, the meanderings of rivers are born of the planetary drama of movement.

Humanity flees from understanding, seeking shelter from changes; they eschew

History and artists exist in constant tension with each other, with not a chance of catharsis. Only history can pass the final judgments that won’t ever reach the artist. History made Johann Sebastian Bach into the greatest composer of the Baroque period, long after both the style and its other adherents had drifted into obscurity. History made Marquis de Sade into a 20th century philosopher, since that’s the era that was defined, both in deeds and in thoughts, by the colossal projects of the new world and the new man for which humanity had to pay in ghastly mechanistic cruelty.

However, artists also hasten history along. It’s their fate: to denominate, to name the surrounding phenomena. Images precede thought, denominate the future and present it to the world, long before these events, these discoveries come to pass. To name is to prophesy, or to warn.

Artists are the nervous system of humanity: they sense pleasure and pain earlier than the rest of the body.

Artists want to hasten the world along. Why else would they work? Even the vainest among them know that the recognition of contemporaries is but an illusion. In the tragic times of drastic and painful social shifts, artists manifest their essence: they are “wounded healers.” The archetype of Verwundeter Heiler was introduced by a Swiss analyst Adolf Guggenbühl-Craig: it evokes the image of Asclepius, the god of medicine in Greek mythology, who himself suffered from physical pain. Guggenbühl-Craig contends that doctors who have personal experience of an ailment can devise more effective therapy, but the experience also makes them more prone to sadistic outbreaks. However, healing is often impossible without drastic measures, and each artist is prone to sadistic violence. He violates the world with his works, which not a soul had asked for.

Guernica by Pablo Picasso is one of the most important works of the type in the 20th century. It is one of the most penetrating and realistic documents of the era of colossal modernist projects of total revolutions that bled over into total wars.

Such conscious violence is typical of the works of Volodymyr Budnikov and Vlada Ralko. They are confident, willful artists, driven by their own sensibilities and the raw will to express, rather than by trends, the logic of an instilled tradition, social demands or even by rational analysis.

Therefore, Budnikov and Ralko cannot be described as a tandem. They stay in dialogue. Yet the dialogue is stripped of all shreds of conformity, both in the microcosm of their conversation and in the broader context of the country or the world. The Shelter Project marks a milestone in their dialogue and highlights its most salient features. Both artists stay true to themselves, and both evoke the catastrophe through their recognizable imagery. There’s no obvious shelter for those caught in it.

Through all the stages of his career, Volodymyr Budnikov’s sensibility was marked by the understanding of the world as an ongoing catastrophe. He explored the motif through landscapes, through the images of nature, which are always born of the strife of elements and organisms. The scholars of Budnikov’s works are often tempted to mention the Baroque style with its catastrophic worldview. For decades, Budnikov has been exploring the future, with all its unpredictable shifts, anxieties and anguishes, through landscapes. His gaze is unflinching, since he knows that life, in all its anguish and glory, is contained in movement. Each tree that breaks out of its seed in a titanic spasm is in movement. Each boulder, the meanderings of rivers are born of the planetary drama of movement.

Humanity flees from understanding, seeking shelter from changes; they eschew

the naming by hiding behind vague phrases, catchy mottoes, vulgarities, and parodies. This is but another reminder that our biological species teeters on the verge of self-destruction.

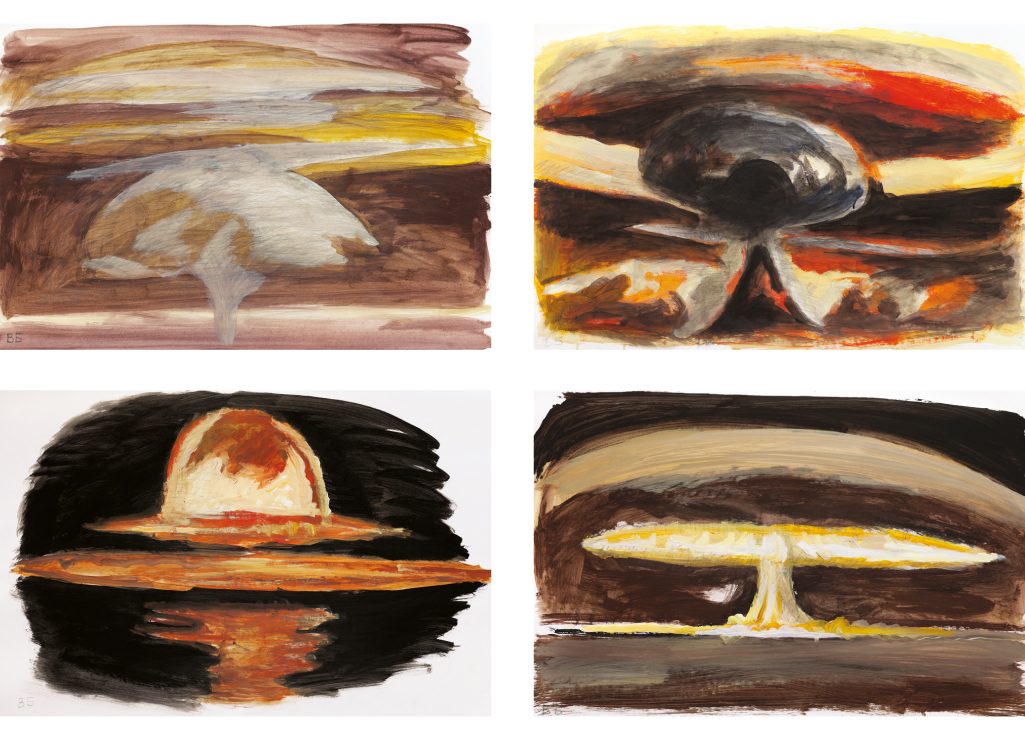

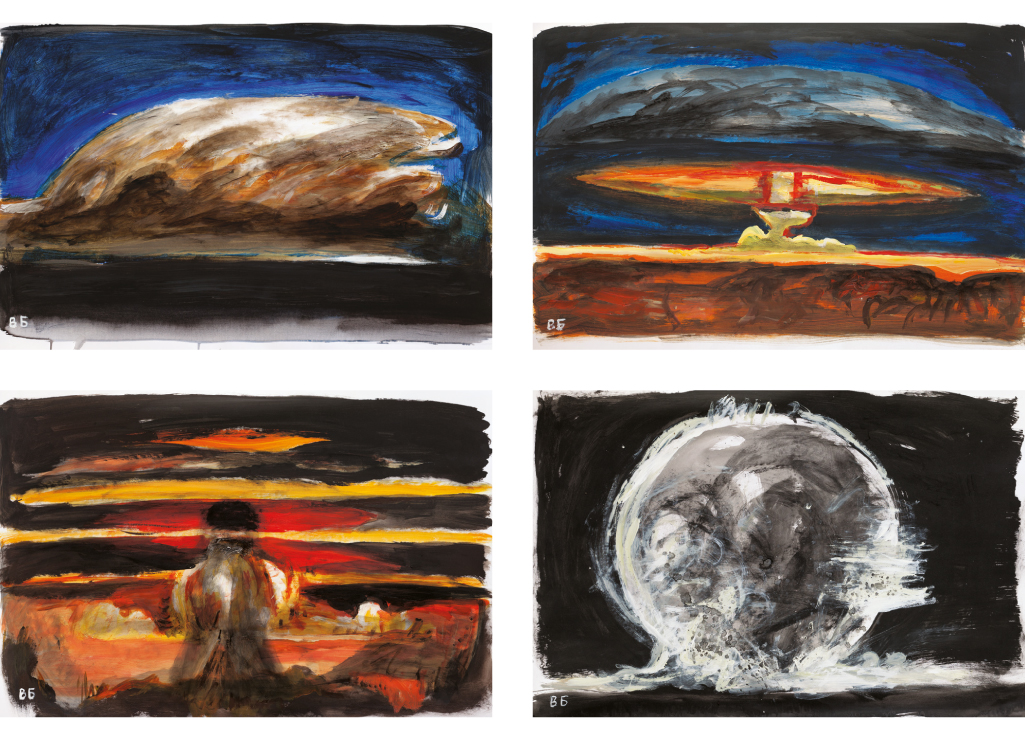

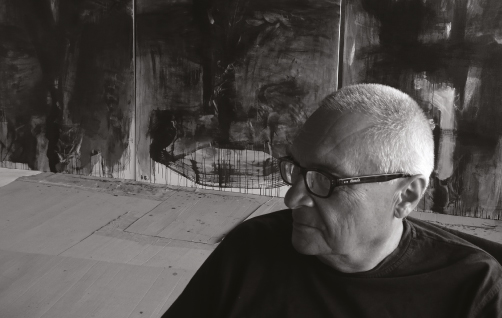

These days, Budnikov’s works erupt into a series of nuclear explosions, and it’s not a warning: he’s merely naming the world. It’s the world that may linger, in all its anguish and glory, but it would be swept clean of people. Within the context of natural elements, a nuclear explosion belongs to the sphere of the aesthetic. It bespeaks the grandeur of natural aesthetics.

The nuclear explosion series by Budnikov offers a synthesis of his landscapes and nonfigurative works. The series is centered upon the will and conflicts. Lines, colours, textures remain in a perpetual orgiastic confrontation. V

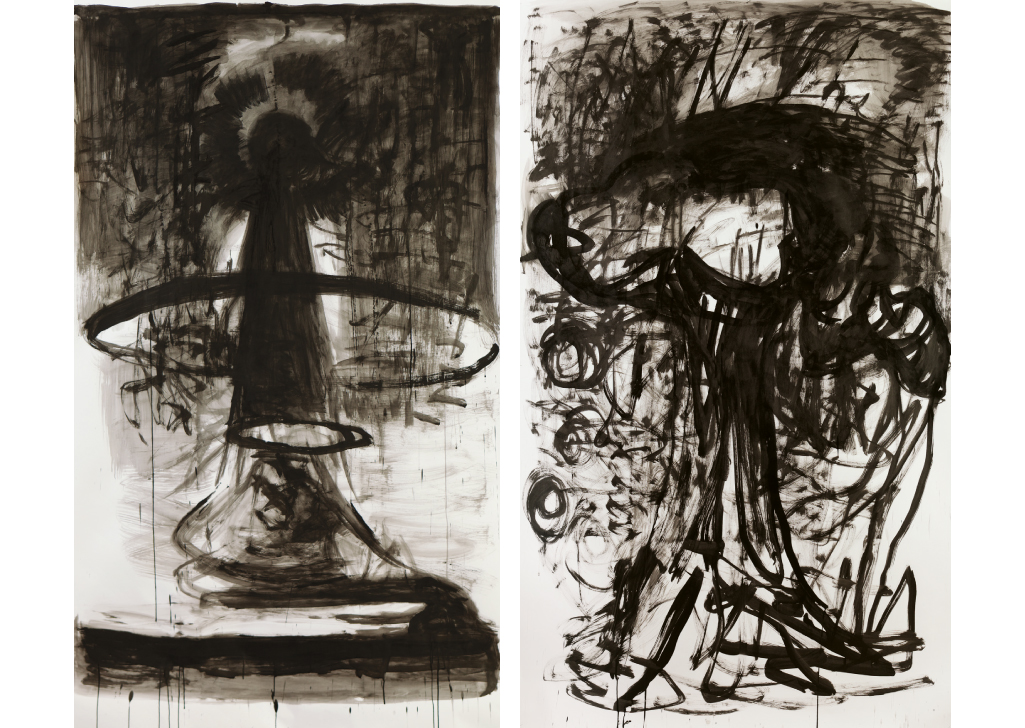

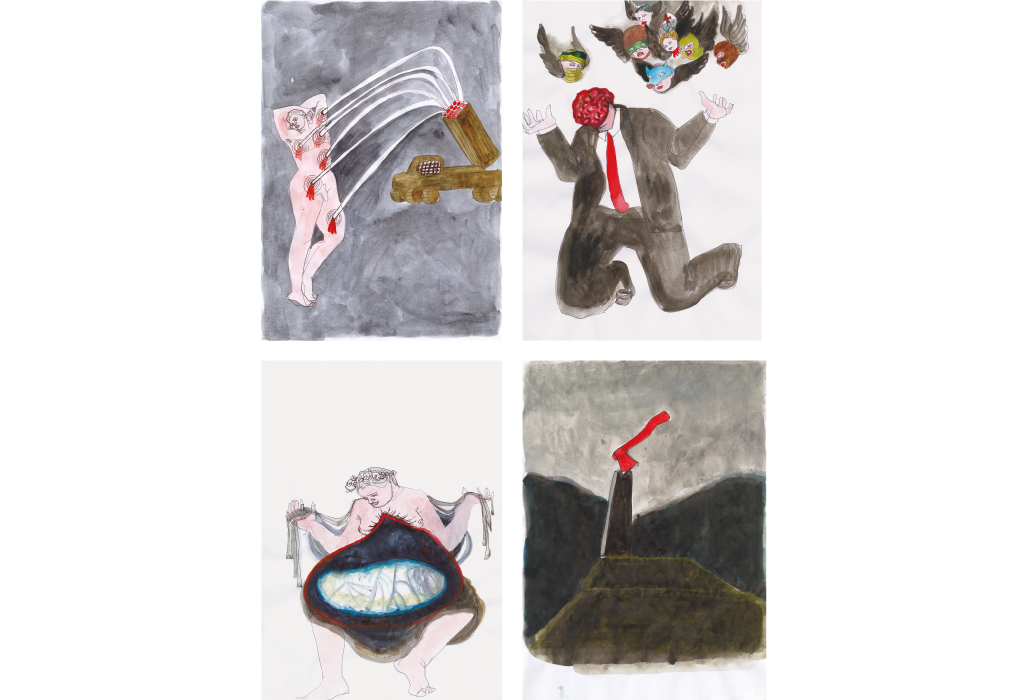

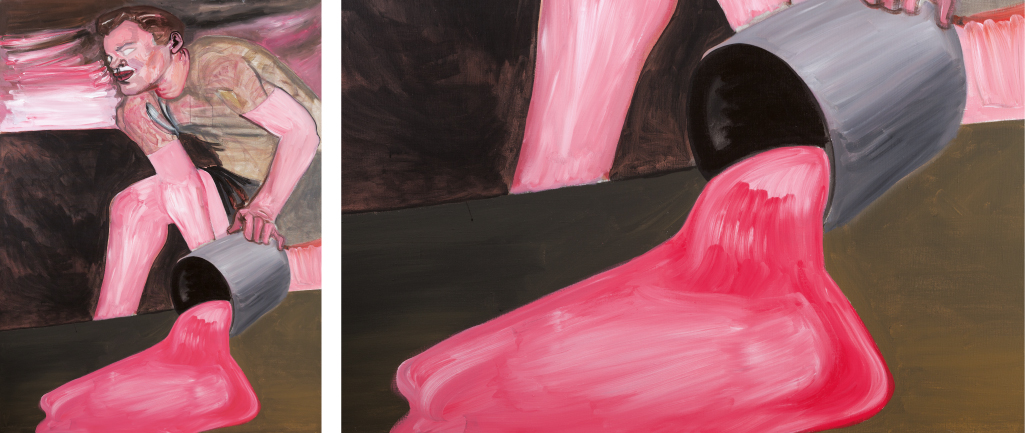

lada Ralko is closer to Gustav Meyrink, a Czech writer who believed that the uncanny and the dramatic, the most eerie demons rein supreme in the quotidian, in the mundane. Budnikov explores landscapes; Ralko denominates sexuality on the crossroads between the biological and the social. Both grant names to the captivatingly uncanny: the inexorability of changes. It’s life, viewed as a series of metamorphoses. The works created for the Shelter series partly overlap with the Kyiv Diary, the cycle conceived during Maidan – honest, powerful, shameless in its despair and startlingly humane in its vulnerability. Meyrink’s image of feet that follow one another in a circle became a mystical metaphor of the rise of Nazism. Rhinocéros by Eugène Ionesco laid bare the anamnesis of a citizen turning into a beast. The prints by Francisco José de Goya depicted the impending darkness of the mind that came to believe that war is the vehicle of technical progress. Similarly, the interplay of biomorphic and zoomorphic beings in Ralko’s works draws our attention to the phenomena that already permeate our existence. There’s no point to seeking shelter from them in the quotidian, since the yearning for the somnolent mundane became the breeding grounds for the bacteria of war.

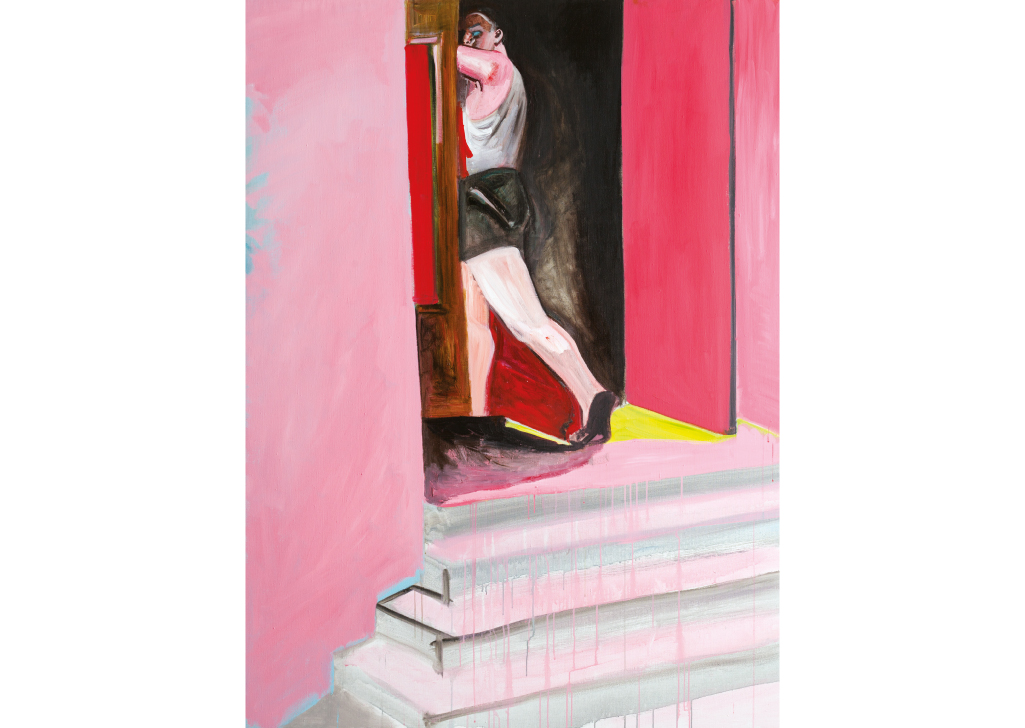

In stark contrast to these drawings, Ralko forgoes direct emotional responses in her paintings of the Shelter cycle. Their unwavering suspense is evocative of Alfred Hitchcock’s films: the anticipation is more horrifying than any actual horrors. The cycle culminates in the landscape with folded umbrellas, the kind you see on beaches or in outdoor cafes. What do these evoke? The closing of a nice day? The closing of a tourist season? Or is it the final, imminent closure?

An umbrella looks like a mushroom. It calls up the absurd aesthetic conciseness of the project of Enver Hoxha, a socialist leader of Albania. At a certain point, he started to propagate the idea that the entire world had turned against Albania, one of the most closed-off countries. Albania was on the verge of nuclear destruction. The citizens were charged with building small family fallout shelters, absurd cement structures that pepper Albania to this day like giant mushrooms. It’s the most grandiose installation of paranoia, a metaphor of mock-shelters.

In Budnikov’s drawings, mushroom clouds spring up like bright lines in a cardiogram. Georges Bataille contended that the ocean is a metaphor of monumental masturbation; similarly, a nuclear explosion may evoke a planetary orgasm, a cosmic catharsis. Sure, nobody will live to see this art object, so you might as well enjoy it while you last.

Our best hope for a shelter, if there is one, lies in trying to come to our senses, open our eyes, break free of the darkness of our own making. Only then will we manage not only to save ourselves, but to also save someone else.

The nuclear explosion series by Budnikov offers a synthesis of his landscapes and nonfigurative works. The series is centered upon the will and conflicts. Lines, colours, textures remain in a perpetual orgiastic confrontation. V

lada Ralko is closer to Gustav Meyrink, a Czech writer who believed that the uncanny and the dramatic, the most eerie demons rein supreme in the quotidian, in the mundane. Budnikov explores landscapes; Ralko denominates sexuality on the crossroads between the biological and the social. Both grant names to the captivatingly uncanny: the inexorability of changes. It’s life, viewed as a series of metamorphoses. The works created for the Shelter series partly overlap with the Kyiv Diary, the cycle conceived during Maidan – honest, powerful, shameless in its despair and startlingly humane in its vulnerability. Meyrink’s image of feet that follow one another in a circle became a mystical metaphor of the rise of Nazism. Rhinocéros by Eugène Ionesco laid bare the anamnesis of a citizen turning into a beast. The prints by Francisco José de Goya depicted the impending darkness of the mind that came to believe that war is the vehicle of technical progress. Similarly, the interplay of biomorphic and zoomorphic beings in Ralko’s works draws our attention to the phenomena that already permeate our existence. There’s no point to seeking shelter from them in the quotidian, since the yearning for the somnolent mundane became the breeding grounds for the bacteria of war.

In stark contrast to these drawings, Ralko forgoes direct emotional responses in her paintings of the Shelter cycle. Their unwavering suspense is evocative of Alfred Hitchcock’s films: the anticipation is more horrifying than any actual horrors. The cycle culminates in the landscape with folded umbrellas, the kind you see on beaches or in outdoor cafes. What do these evoke? The closing of a nice day? The closing of a tourist season? Or is it the final, imminent closure?

An umbrella looks like a mushroom. It calls up the absurd aesthetic conciseness of the project of Enver Hoxha, a socialist leader of Albania. At a certain point, he started to propagate the idea that the entire world had turned against Albania, one of the most closed-off countries. Albania was on the verge of nuclear destruction. The citizens were charged with building small family fallout shelters, absurd cement structures that pepper Albania to this day like giant mushrooms. It’s the most grandiose installation of paranoia, a metaphor of mock-shelters.

In Budnikov’s drawings, mushroom clouds spring up like bright lines in a cardiogram. Georges Bataille contended that the ocean is a metaphor of monumental masturbation; similarly, a nuclear explosion may evoke a planetary orgasm, a cosmic catharsis. Sure, nobody will live to see this art object, so you might as well enjoy it while you last.

Our best hope for a shelter, if there is one, lies in trying to come to our senses, open our eyes, break free of the darkness of our own making. Only then will we manage not only to save ourselves, but to also save someone else.

The author would like to express his gratitude to his colleague Lesia Hanzha for the discussion about art, scholarship and chaos at the XXII Lviv International Book Festival that provided the necessary impetus for the text.

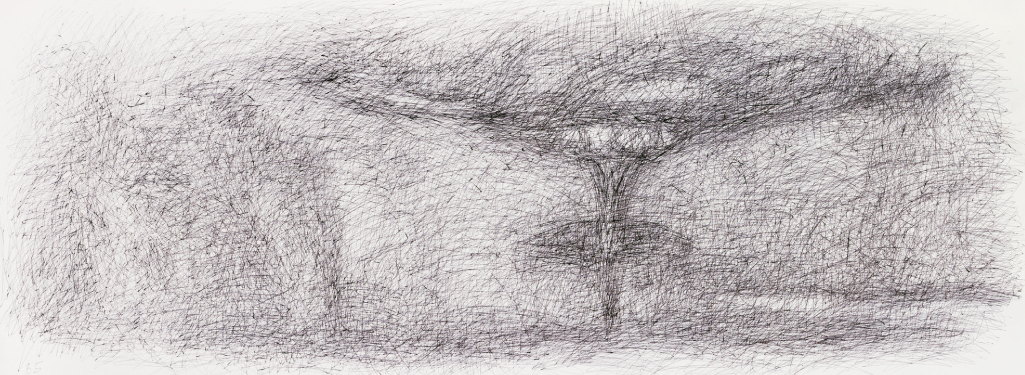

First, I drew a nuclear explosion like a tree

with a spreading crown that sheltered

iconic characters of classical paintings.

However, the parallels between mushroom

clouds and trees in pastoral landscapes,

or with giant umbrellas, were so expressive

that I concentrated exclusively on these

dangerously exquisite silhouettes. It’s not

the explosions that bespeak the changed

world in which we are all trapped: it’s this

uncanny parallel.

Sketches

2015, 42х30, ballpoint pen on paper

Explosion

2015, 30х120, ball pen on paper

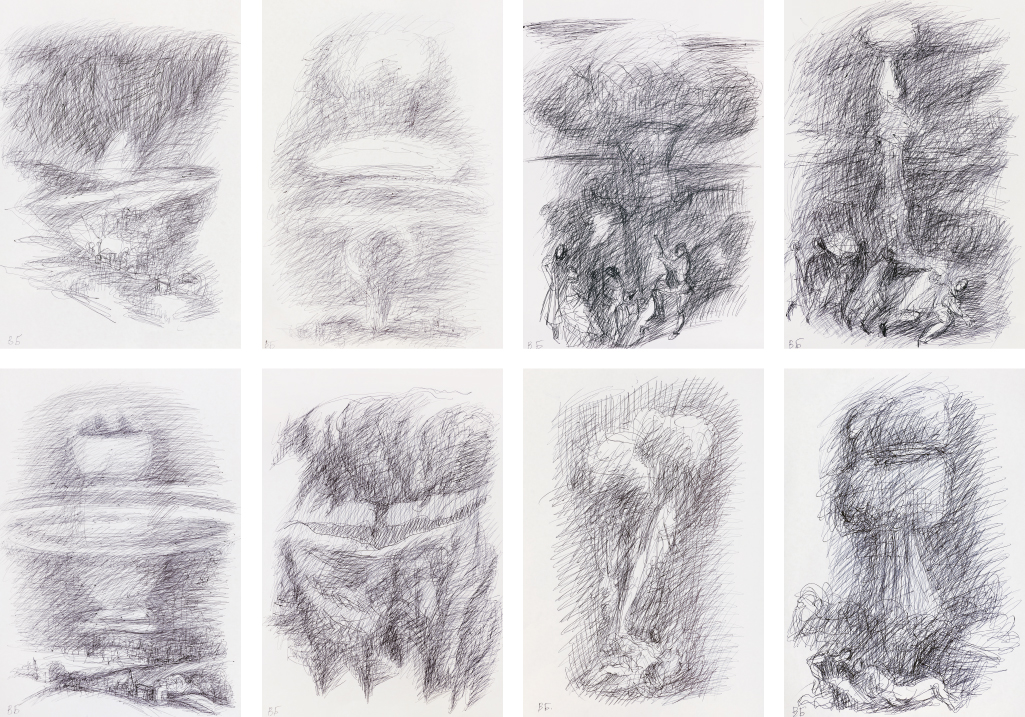

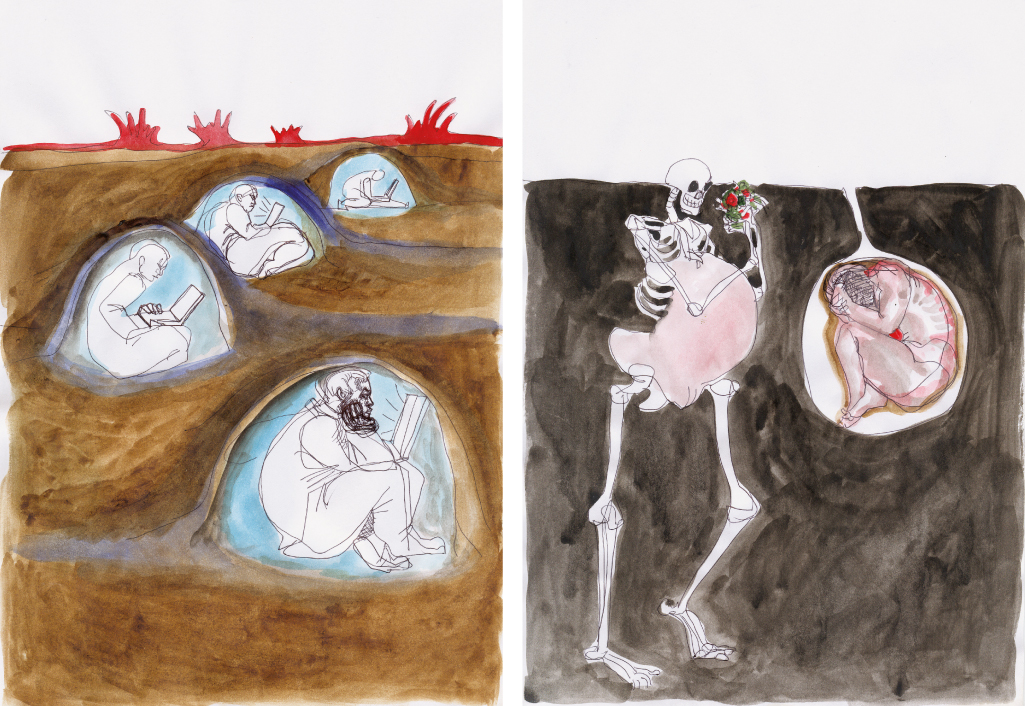

With a war that’s not even called a war

in the background, mundane, peaceful

objects seem to come to a boil, as if you

were examining quotidian things through

the screen broadcasting the latest news.

Even misleadingly unchanged objects

are imperceptibly different. Our normal

surroundings screech out warnings, even

as they seem to exude calm. War appears to

have seeped under the skin of our peaceful

life, and it can break through the surface

of any mundane scene. There’s a hint of

disquiet in a picnic on the beach, a roof

being renovated, an evening stroll.

From the

KYIV DIARY

series

2015, 29,7х21, watercolour, ballpoint pen on paper

Can the judgments of artists matter and

effect changes in times of emergency? The

issue is so complicated that we had to set

down, to the best of our ability, everything

that was said on the matter, before we

could so much as try to comprehend it.